- Details

- Created: Thursday, 25 July 2013 13:25

Taddeusz Nowak, from Hamtramck, Mich., entered active military service on Sept. 28, 1936. He joined the U.S. Army Air Corps and became a member of the 17th Pursuit Squadron stationed at Selfridge Field in Michigan. On Oct. 31, 1940, Pvt. Nowak and the rest of the 17th Pursuit Squadron were sent to the Philippine Islands to beef up the U.S. Air Corps presence in the Pacific. He was stationed at Nichols Field on Luzon and split his time between training and enjoying the tropical climate.

On December 8, 1941, the Japanese attacked Nichols Field and damaged many of the 17th’s aircraft. Most of the unit’s members turned into infantrymen charged with helping defend the islands against the Japanese invasion. Unfortunately, the Japanese military proved to be too strong at that time. The Battle of Bataan and, later, Corregidor, were soon lost.

Like many other American serviceman, Pvt. Nowak was captured and had to endure terrible treatment at the hands of his Japanese captors from roughly May 1942 until October 1944. Somehow, Pvt. Nowak survived the early part of his ordeal. In October 1944, though, he became part of one of the U.S. Navy’s largest military disasters.

As U.S. forces started operations to re-take the Philippine Islands, the Japanese moved prisoners out of camps and onto ships. Their final destination was to work as slave labor in Japan and Japanese-occupied territory. One such ship was the 6,886-ton freighter Arisan Maru. On Oct. 20, 1944, the Arisan Maru left Manila headed for Takao Formosa. Conditions on the ship were atrocious with 1,782 U.S. military Prisoners of War (POWs) crammed into filthy cargo holds with little food and water. Temperatures rose to over 100 degrees in the cramped quarters. Many men died in their own filth and some went mad. This ship was one of a series of Japanese cargo freighter’s that would be aptly called “Hell ships” by the US servicemen who survived the journey. Unfortunately, Pvt. Nowak was one of the poor souls held in this ship’s cargo hold.

On Oct. 24,1944, the Arisan Maru was sighted by the U.S. Navy submarine USS Shark (SS314). The Shark fired its torpedoes and the ship went to the bottom with a total loss of 1,775 prisoners of war, including Pvt. Taddeusz Nowak. As the ship sunk, the Americans swam toward neighboring Japanese vessels. Enemy sailors and Army personnel beat back the POWs. Many of these men could have been saved, but were left to drown by the Japanese military forces. As with all the Hell Ships, there were no markings on these ships to identify them as carrying POWs, so the captain of the USS Shark had no idea that prisoners were aboard. To this day, the Arisan Maru sinking is still the greatest loss of U.S. military lives in a single military sinking.

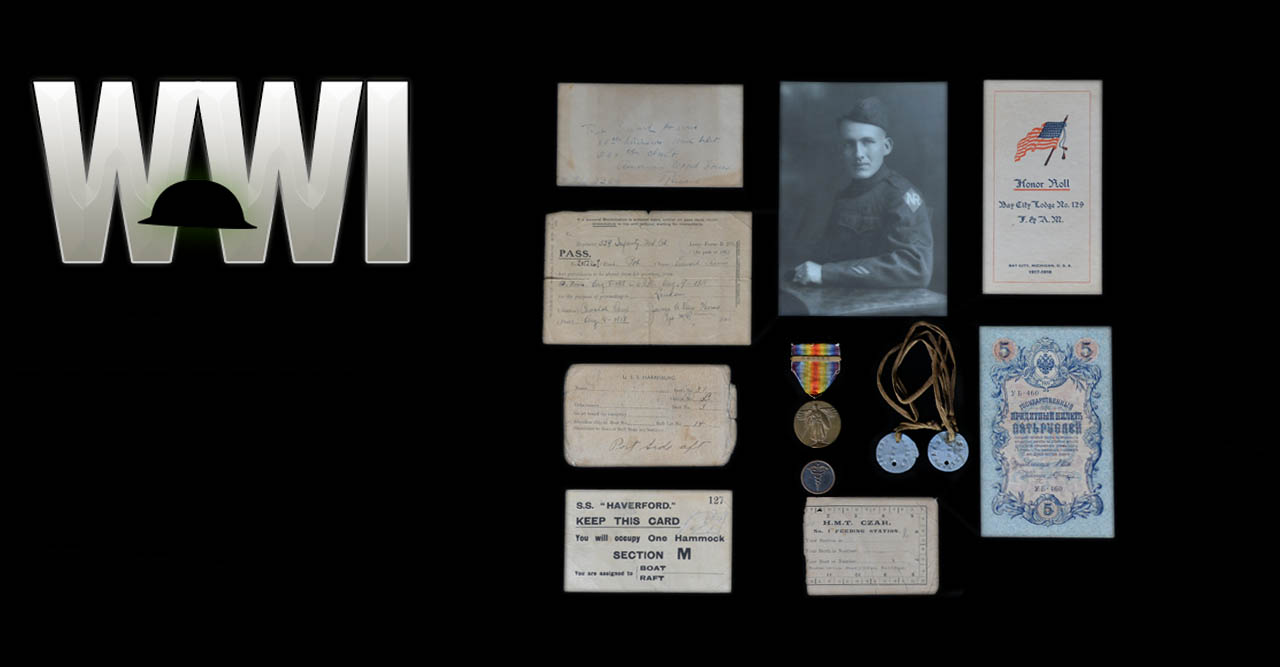

We are very proud to have and display the Pvt. Taddeusz Nowak “killed in action” military collection. It is a fitting tribute to a special individual who was strong and skillful enough to survive two years of the most horrible treatment ever given to any countries prisoners of war in history. It is truly sad that he met his end in such a tragic turn of events.

On December 8, 1941, the Japanese attacked Nichols Field and damaged many of the 17th’s aircraft. Most of the unit’s members turned into infantrymen charged with helping defend the islands against the Japanese invasion. Unfortunately, the Japanese military proved to be too strong at that time. The Battle of Bataan and, later, Corregidor, were soon lost.

Like many other American serviceman, Pvt. Nowak was captured and had to endure terrible treatment at the hands of his Japanese captors from roughly May 1942 until October 1944. Somehow, Pvt. Nowak survived the early part of his ordeal. In October 1944, though, he became part of one of the U.S. Navy’s largest military disasters.

As U.S. forces started operations to re-take the Philippine Islands, the Japanese moved prisoners out of camps and onto ships. Their final destination was to work as slave labor in Japan and Japanese-occupied territory. One such ship was the 6,886-ton freighter Arisan Maru. On Oct. 20, 1944, the Arisan Maru left Manila headed for Takao Formosa. Conditions on the ship were atrocious with 1,782 U.S. military Prisoners of War (POWs) crammed into filthy cargo holds with little food and water. Temperatures rose to over 100 degrees in the cramped quarters. Many men died in their own filth and some went mad. This ship was one of a series of Japanese cargo freighter’s that would be aptly called “Hell ships” by the US servicemen who survived the journey. Unfortunately, Pvt. Nowak was one of the poor souls held in this ship’s cargo hold.

On Oct. 24,1944, the Arisan Maru was sighted by the U.S. Navy submarine USS Shark (SS314). The Shark fired its torpedoes and the ship went to the bottom with a total loss of 1,775 prisoners of war, including Pvt. Taddeusz Nowak. As the ship sunk, the Americans swam toward neighboring Japanese vessels. Enemy sailors and Army personnel beat back the POWs. Many of these men could have been saved, but were left to drown by the Japanese military forces. As with all the Hell Ships, there were no markings on these ships to identify them as carrying POWs, so the captain of the USS Shark had no idea that prisoners were aboard. To this day, the Arisan Maru sinking is still the greatest loss of U.S. military lives in a single military sinking.

We are very proud to have and display the Pvt. Taddeusz Nowak “killed in action” military collection. It is a fitting tribute to a special individual who was strong and skillful enough to survive two years of the most horrible treatment ever given to any countries prisoners of war in history. It is truly sad that he met his end in such a tragic turn of events.